The folks at Inliquid interviewed me and all of the other artists in You Are Here.

Here’s my interview:

And here’s a complete walkthrough of the exhibition with all of the artist interviews:

The folks at Inliquid interviewed me and all of the other artists in You Are Here.

Here’s my interview:

And here’s a complete walkthrough of the exhibition with all of the artist interviews:

Hey friends!

I’m still here, noodling around. Mostly I’m working on a novel. Without explaining too much about it:

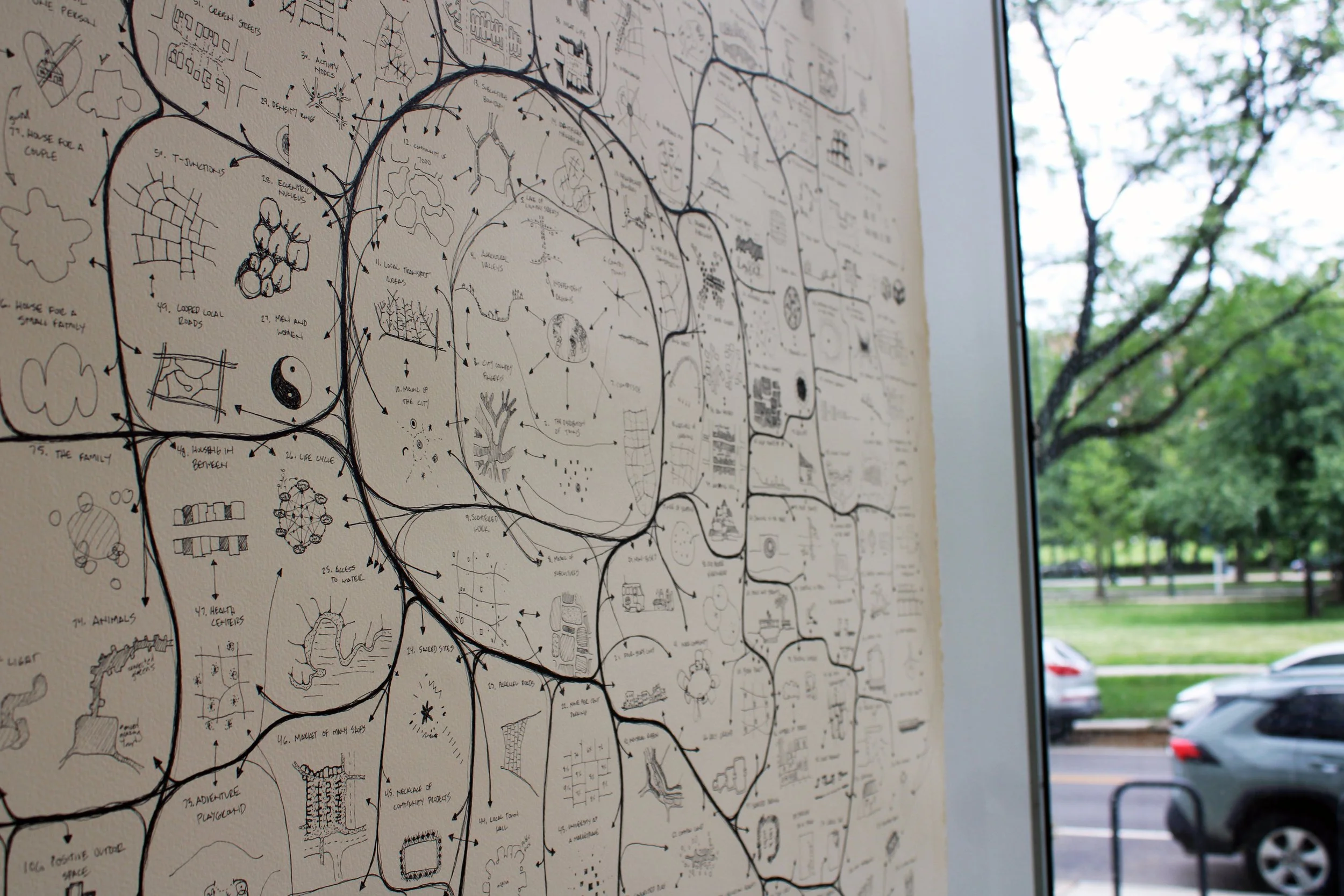

The novel will be using (very loosely) the connective web around A Pattern Language to structure how different chapters/passages get tied into each other. That’s what this drawing was all about.

Mapping a Pattern Language, 2020

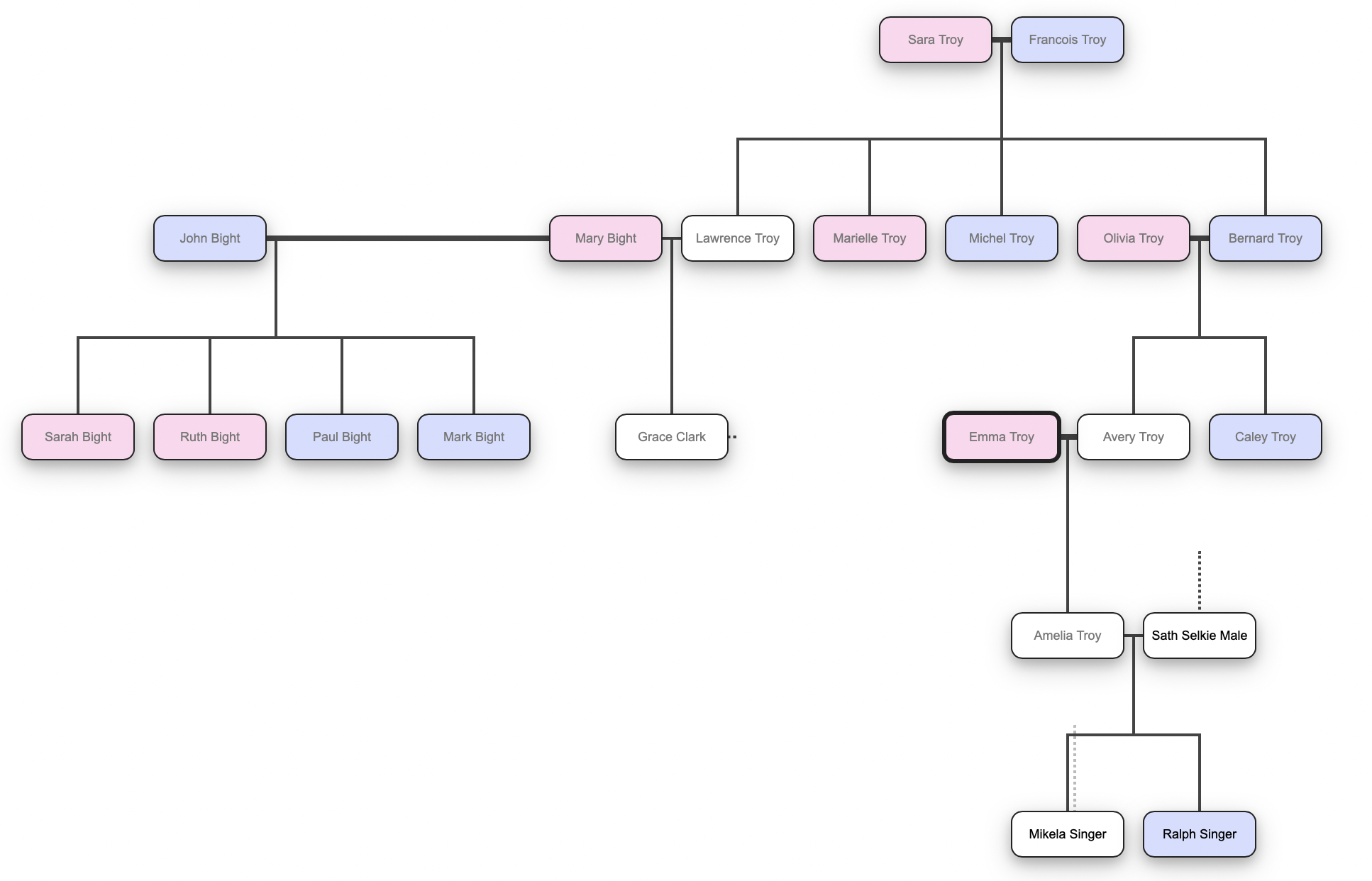

It’s set in a fictional town called Rock Harbor and the legend of the selkie is a through line of the novel. The story is multigenerational, so I’m doing some family mapping.

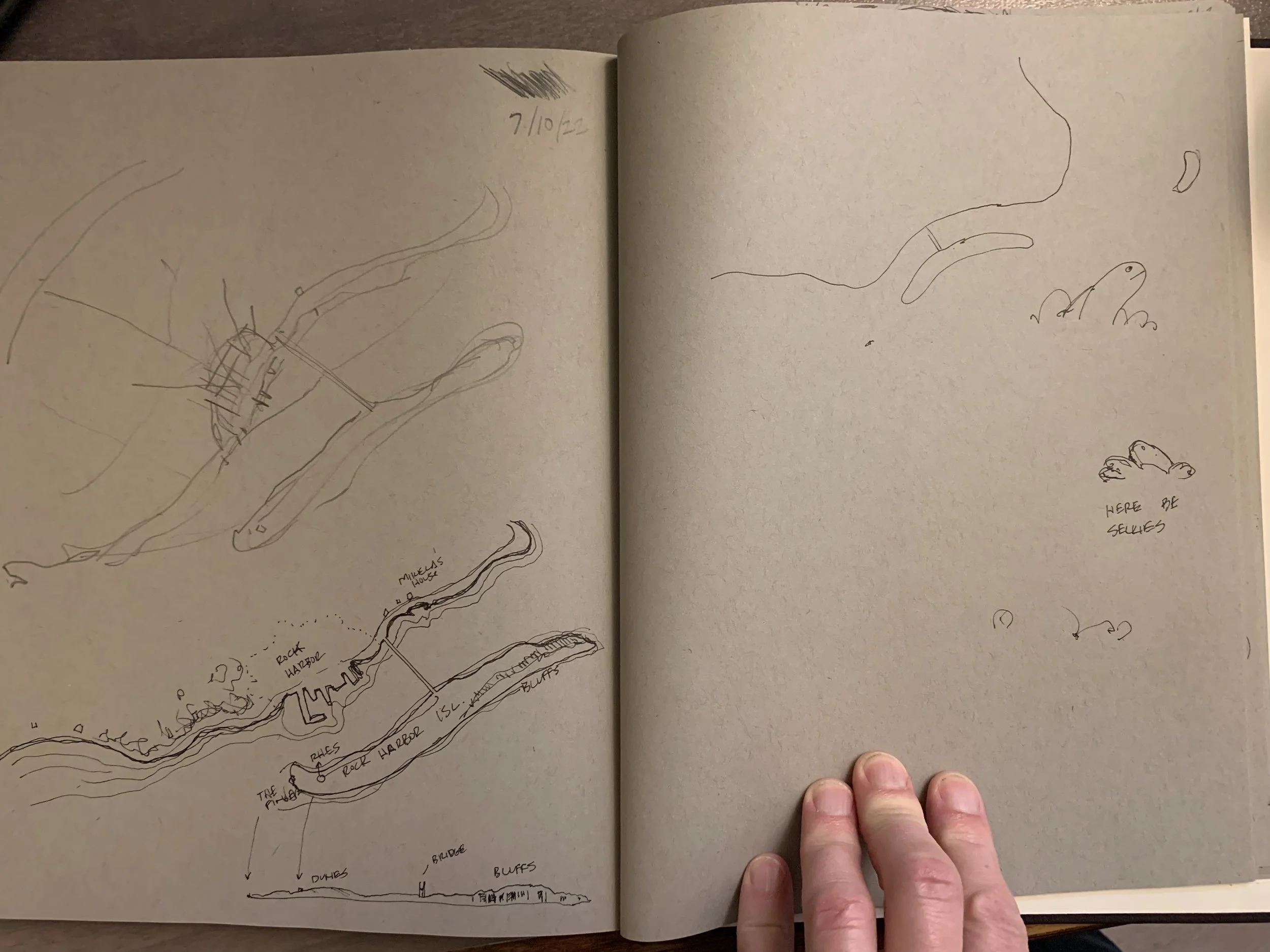

And lately I’ve been mapping out what Rock Harbor (one of the main settings) actually looks like.

I’ll include here a passage, a story within a story, that one of the characters finds in a local library.

Sea Shanties and Ghost Tales: an Anthropological Treatise on Maine Maritime Myth

By Charles Demuth, Esq.

Chapter 18: Selkies in Downeast

1888, Rock Harbor

In March of 1888, Lawrence Troy, a Sailor attached to the ship Bright Horizon, was ashore for a fortnight while the ship’s riggings were being mended down at Hawke’s Shipbuilders. Most times the Bright Horizon anchored in the bay, it was just long enough to unload catches and load fresh provisions, but a few times a year, work more in the nature of repairs was deemed necessary, and this was one such occasion.

Now on shorter shore leaves, young Larry would do what most sailors did, which was to wreck himself in one of the many dockside bars that catered to his sort, but during the longer periods ashore, he had a woman north of the village by the name of Mary Bight, whom he would visit.

Mary herself was the wife of a captain named John Bight, whose ship went much further than the local fisher boats or clippers used for messenger service to ports south, like Boston and New Bedford. So Mary was often alone, and young Lawrence could quite easily take the woods way uphill to High Street, where her house sat by the pond, the Widow’s Peak overlooking the village and the bay. Larry would slip in through the servant’s entrance, up the back stair to the Master Bedroom, where Mary waited. We need not detail the particulars; but needless to say that this arrangement suited both Larry and Mary very much, and it went on for some years, even as Mary and Captain Bight brought five children into the world.

Four of the children were ordinary young souls, two girls and two boys - Sarah, Ruth, Paul and Mark, all with reddish-brown hair that recalled the Captain’s once bright red hair, now gone grey.

The fifth and youngest child was a girl named Grace. She had a big head of curly blonde hair, green eyes and a round face that, in a small village like Rock Harbor, made clear for anyone to see her true parentage lay not with the Captain but with the young sailor.

This tale would perhaps be in the mold of so many others, a story of infidelity and its aftermath, if it were not for the sudden disappearance of young Larry and Grace one fine spring day in early March.

For the Troys were an old family in Downeast, long working in the fishing trade, rarely if ever straying from Rock Harbor. An old family but not a reputable one. For as long as anyone could remember, the Troys had a propensity for sudden disappearances and equally sudden and mysterious returns, years later, in the worst of weather, showing up naked ashore without a boat in sight.

The Troys mostly stuck to themselves, and when asked about the oddness of their comings and goings, would keep their silence. About as talkative as stones, some of them.

Young Larry had been the first of the Troys in living memory to woo anyone in town. The Troy spouses typically came and went without so much as an explanation for where they came from and where they were going.

Now March 1888, Grace was then fourteen years old. Larry still came to see Mary oftentimes, but after Grace was born, he began to come in through the front, as the Captain and his wife’s invited guest. There was much speculation in Rock Harbor Village about this arrangement. The Captain was too important and wealthy a figure in town to challenge, but it was clear that the manner of living he had chosen, in accommodating adulterers in his home, was not the correct way of things.

Things can go two ways in a village like Rock Harbor. Either a scandal results in the besmirchment of all concerned, or for reasons only known to themselves, the townsfolk decide, without even really any debate, that the particulars of the unusual situation are just going to be accommodated without further comment, and then the arrangment simply becomes a part of the local landscape - not discussed, and all conversation around the subject swiftly redirected.

The good, honest folk of Rock Harbor had decided in favor of the second option, being the simplest and most expedient. Gossip is quite a natural thing in a small village, but in coastal communities it competes with the naturally taciturn nature of fisher folk, so in truth the thing could have gone either way. Whatever the reasons, Rock Harbor had, since Grace’s birth, pretended not to notice the bright flaxen hair or green eyes that marked her so obviously of Troy blood.

What your faithful narrator tells you now comes from several reliable sources who were present on the morning of March 14th of that year.

That morning was sunny and clear, having been the day after a blizzard hit all of New England, which was later called “The Great White Hurricane”. The winds and surf during the storm had been strong enough to knock over boat houses at the piers, and several boats took damage.

So when Larry Troy and Grace Bight were seen coming down out of the woods to step onto the north road out of the village, Larry still in his fisherman’s gear, and Grace in the tan work apron she used when gardening, there were not a few folk out in the village, repairing shutters and windows, or drawing boats up onto the sand to fix masts, and there were a few work crews puzzling over how to pull the boat houses back together with the parts remaining to them.

All of this is to say that there was an audience.

One reliable witness has told this narrator that the pair looked as if in a spell. They walked with purpose, without speaking, holding hands, bright green eyes only on the road north. Both were barefoot. And Larry was missing his cap.

One could spin a romantic yarn around their departure as the father finally come to claim his daughter. Indeed, some have, and in some tellings of this tale that’s how the story ends. You may have heard the most common telling: that the two stepped into Larry’s little punt and rowed off into the fog, and were seen years later settled in Nova Scotia, out of Bridgewater.

There is also a version that goes something like this: Captain Bight rode on horseback to cut them off north of the village, and killed the both of them. It’s a popular enough tale; being one that taps into folks’ not incorrect belief that with power comes abuse of the common people.

The truth, as told to this narrator, is stranger.

For the odd couple’s behavior was so disturbing that most of the townsfolk present followed them north. In the wintry aftermath of the storm, Larry and Grace walked at an even, slow pace, their bare feet crunching in the wet snow, but they seemed not to notice the cold.

There were quiet, unsettled murmurs as the village folk followed, bundled up in their coats and scarves and mittens, but mostly those present were as quiet as those they trailed behind.

A mile north of the village, Larry and Grace turned into the little cove that sits in front of what is today the Harris house, but back then belonged to the Wyatts. The sky was bright against the rolling sea as they walked down to the shoreline, their bare feet pushing through the snow into the black sand. Grey seals swam about in the cove, as they often did, it being a natural shelter, but when Larry and Grace put their feet into the surf, the seals all seemed to swim closer. The ones on rocky ledges dove in to follow the others.

The father and daughter walked straight into the water.

Up to their knees.

Up to their waists.

Up to their chests.

Up to their necks.

They walked straight in until their heads were completely submerged, and then they were gone, with only the circling seals remaining, and the gulls diving and darting above.

Why, you might ask, why didn’t anyone rescue them?

It is, dear reader, a perfectly sensible question, if this were the only time in the history of Rock Harbor that folks have been Called to the sea.

But it isn’t.

And it isn’t the end of the story, either.

On November 14, 1898, after the Portland Gale, a farmhand by the name of Glenn Fontine came south to Rock Harbor on horseback, on his weekly trip to purchase sundries from the general store. On the way he found a woman, wrapped in seaweed and braken, laying naked on the very same black sand beach where Larry and Grace had disappeared some ten years before.

Glenn found one of the Wyatt boys, and together they carried the woman up into the Wyatt house and laid her out on the guest bed. She was alive, to be certain, but not aware of the world around her. Her skin was pickled all over, with a mottled grey color that over the course of the day began to fade, as if her blood were warming and the skin tinged ever pinker.

The natural and first conclusion, if you hadn’t heard the beginning of this tale, might be that the poor woman was a shipwreck survivor.

Those do happen from time to time, though less often than you hear in stories. Once in a long decade you might have survivors from a wreck swim to shore alone; most commonly, though, survivors come in on dinghies and life boats.

You have to take into account that this was after a November double storm, a blizzard and hurricane. The water was frigid. No one survives the sea in those conditions.

Except the woman who washed ashore that cold November day.

It wasn’t until Mrs. Wyatt arrived - she came hurrying home from the village at the news - that a name was put to the young woman.

For ten years before, Mrs. Wyatt had seen this woman - who now laid on a bed in her own home - walk into the sea.

The woman was Grace Bight, no doubt, but no longer a girl now. Her hair was long, tangled about her, as if it had never been combed, and there was seaweed wrapped about her head almost like a scarf. The woman’s face was unmistakeable.

Mrs. Wyatt cleaned Grace up as best as she could, dressed her in one of her own nightshirts, and laid her under blankets. She put her oldest daughter on watch to check in on the woman often, and then she borrowed a horse from a neighbor and rode to Machias for a doctor.

Grace slept for three solid days, seemingly needing no food or water or care, though steadily she seemed to come back to health.

On the fourth day, she opened her eyes.

Finally, hi!

Transition for me has mostly happened behind the veil of Pandemic, so a good number of you I haven’t seen in person since…geez…2019. Still transfeminine/non-binary glorious weirdness going on over here, but I’m not torn up about it these days. Just a thing.

Best,

Colleen

I have several older sculptures and a newer drawing in this exhibition curated by Clare Finin for InLiquid. Exhibition details are here. Exhibition is on view until October 1 2022.

Heaven, 2001, 84” diameter, wood, plastic, flocking

From the press release:

From studying the buildings we populate, to the bodies we inhabit, to how we navigate the world at large, You Are Here explores themes of mapping and placemaking. In this exhibition, a group of seven artists take on various approaches to these themes to examine the places where we live, work, and play as a way to gain insight into our collective needs and aspirations.Jennifer Johnson, Paul Fabozzi, Maria R. Schneider, and Miriam Singer reflect on and analyze our constructed surroundings. Fabozzi’s paintings highlight the epic structures from around the world, from Rome, to London, to Berlin. Johnson has made a special homage to Park Towne Place itself, and the larger movement of Mid Century Modern architecture for this exhibition: two ceramic installations that map the Park Towne Place campus itself, as well as the downtown boom of mid-century apartment buildings in Philadelphia, and the idealism that it represented. Singer and Schneider also honor the architecture of Philadelphia with their paintings and lasercut constructions, respectively.

Mia Rosenthal zooms out to a galactic view, reminding the viewer that they are dwarfed by the cosmos. Deirdre Murphy’s works keep the viewers in outer space, highlighting the celestial constellations above us and contrasting them with the light pollution emanating from Earth. Conversely, Colleen Keefe’s large-scale works take us to a micro level, inside ourselves; mapping imagined places as a way of investigating our own bodies and constructed identities.

From the embodied, to the environment, to the galactic, the included artists use their respective talents to delineate the places that we exist in in their different forms.

Exhibition photo credit: Abbe Foreman Photography (abbeforemanphotography.com).

Hey folks!

I have a small drawing published in Issue 9 of KHÔRA Magazine, an online arts space featuring writers and artists.

Issue is out now; you can find it here:

https://www.corporealkhora.com/2021/9/issue-9

And you can subscribe on Substack!

Hello folks!

A not so brief explanation for why there’s a new writing section in my portfolio.

So my creative practice over the past 6 months has been almost exclusively writing. Why, you might ask, the sudden switch to something completely new? The answer is that it isn’t really new for me…just almost entirely forgotten.

A long, long time ago (we’re talking early twenties here) I had two creative practices: poetry and sculpture.

I majored in Fine Art at Washington University in St. Louis, and by Junior year had settled on sculpture as the direction I wanted to head in. I still needed to fill out my academic calendar with language arts, though, and so in spring of 1989 I enrolled in a poetry class with Donald Finkel. And then another.

And I discovered I loved poetry. I loved the way language worked, the way words fit together. It felt visceral; it gave me the same sensations I felt making visual art, when something came together just so. I understood it.

I was also not bad at it.

Halfway into my senior year Don took me out for a beer at a blues bar in University City. He was a great guy, a big booster of students he believed in, and I think this was his way of providing mentorship outside of the classroom experience. Don told me that when he was younger, he had to choose between visual art and writing, and chose writing. He said that it was hard to do both, that he couldn’t do it, but wanted to see me succeed if I could. He was very encouraging. He was, I learned much later, at the end of a 30 year run teaching at WU and about to retire, so I imagine he was in a period of reflection on his own career. On retirement in 1991, he returned to sculpture.

I was 20 or 21, and at the time I had it in my head that there was nothing standing in the way of pursuing whatever creative practice I wanted. I didn’t, of course, know then what life throws at us, the ongoing weathering of the soul that shapes us as we swim through the years, what we carry forward and what we leave behind.

I continued to write as a separate creative practice until I was 23 or so. For a few years the work merged with my sculptural practice - words appeared on my pieces. That work now exists only in 35mm slides buried somewhere in our basement. Sculptors tend to be less archival about their work than other disciplines - it’s literally too much baggage to schlep through life.

But at some point in graduate school, the work went silent. I applied to a few visual arts graduate schools, but I also threw in a writing program - the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I said to myself, “well, if I get into that, then I have some decisions to make”. I didn’t, and when I arrived at Cranbrook, the words started to leach out of the visual practice.

It wasn’t a bad thing - my work was evolving, and grad school is about cycling through rapid changes. This was one of them. But as a consequence, close to three decades sit between the last time I took writing seriously and the next time I committed to it.

Enough time has passed that even the physical act of writing has changed for me. The last time I wrote a poem prior to now, I did so on a typewriter. It wasn’t even electric. I would type, cross out and write in lines with a pencil, then re-type the whole thing. Having taken up writing again, I find I miss that. Not enough to actually drop this laptop, of course! But the tactility of high quality paper as you yank it out of the carriage, the feeling of letters on the page…I miss that. It’s like driving a stick shift.

There’s another angle here, of course. I’m quite aware that poetry wasn’t the only thing I set aside when I was young. Writing is in some way connected to my experience as a trans person. There’s a lot to unpack there and I’m not going to do that today - this entry was just meant to be my attempt to explain why there’s a new writing section on my website.

But am I actually good at writing?

I don’t know and no longer much care, I guess. You can read this stuff or not, your choice! This website has veered sideways as my own creative career has twisted around. It used to be much more of a marketing tool; now it’s more like an ongoing document of my experience. I think I like it better that way.

Back in January, before COVID sank its teeth into the world, I applied for a bunch of residency programs, and got into one. When things started getting real in April, pretty much every residency shut down for obvious reasons, and my plans to go to Arts, Letters and Numbers in August were tanked.

It wasn’t a big deal; everyone’s plans for 2020 have gone awry.

Originally my thinking was that getting away to work would be an opportunity to meet a bunch of new people, and part of the appeal of that was simply meeting people who would only know me as Colleen. I was also looking forward to collaborating with folk in a shared studio space. It was a different way of working that I thought would shake things up for me. So, I would miss this opportunity; fine. I had a job, so did Andi, we were healthy and had a roof over our heads. There are much worse things to be worried about, and not being able to go to a residency felt a little like my privilege talking.

But as the year kept going, the fatigue of the sameness of life was beginning to get to all of us.

Then ALN started what they called a Pilot Light program, an informal low occupancy, socially distanced residency option. It was really just to keep the place ticking over until next year - bad things happen to unoccupied old houses, and besides, I think it was a way for them to keep the dream of it alive. They emailed people who’d previously been accepted, explaining the idea and the COVID restrictions that would come with it (quarantine beforehand, masking, no shared food, no visitors - all the sensible things and in line with NYS COVID policy).

After talking it through with the family, I decided to go. It wasn’t going to be the experience I’d originally thought - shacked up with 30 other artists in a giant house making art. But it was still something different.

I had two weeks. I spent the first week working on a mapping of A Pattern Language, and the second week writing (I’m writing a long-form fiction piece whose working title is “My Ridiculous Novel”, because it’s ridiculous that I’m doing it).

The three other residents were laid-back and friendly, and between us we had something like 10,000 square feet and a 6 bedroom house, so there was plenty of breathing room. I was grateful and thankful for the opportunity for a brief respite from 2020, even if it meant I missed the Philadelphia celebrations when Pennsylvania was called for Biden.

As of a week ago when I left, they were still looking to continue the program with new residents, but who knows with the COVID numbers climbing. If you’re interested I can put you in touch.

Here are some photos from ALN.

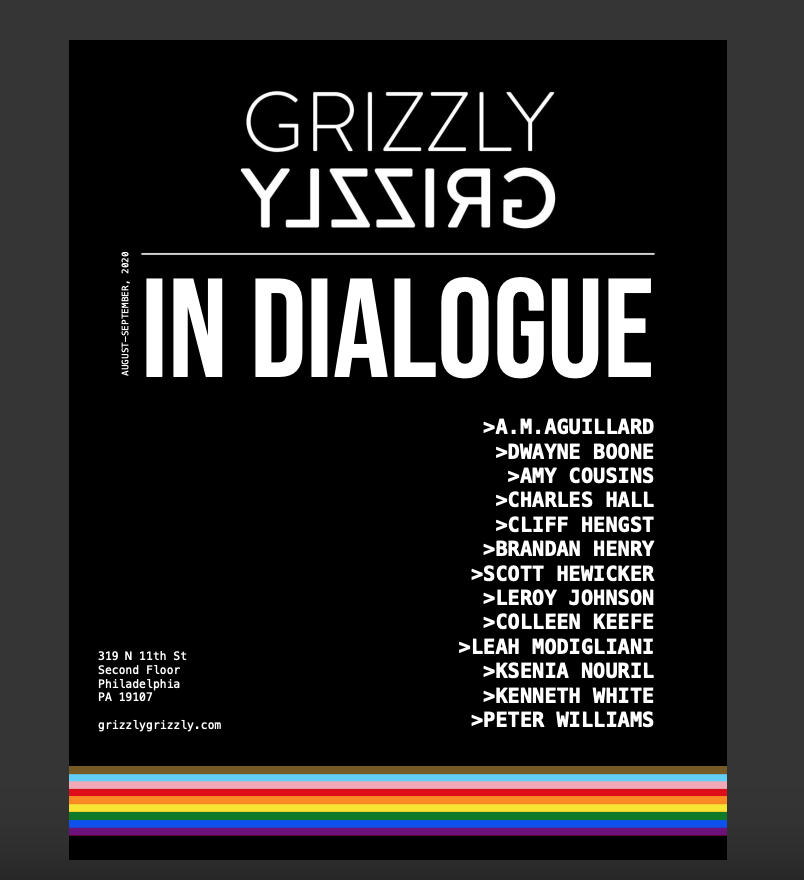

I wrote a piece on being trans, and the various intersections of privilege, for Grizzly Grizzly’s In Dialogue.

It’s here on ISSUU.

Hey Folks,

I posted a little while back about me being trans, and my name change.

In that post I kind of kept it brief, so I thought I would share a little more. This post is just about what’s going on in my head and where I’m at right now; of course there’s the much bigger picture of how I’m negotiating the world with all of this, but that’s for another day. There’s also the background of where these feelings came from, but I think that story has been told enough that it would sound pretty familiar.

Because my mode of transition is gradual, feeling my way toward “me”, rather than having a specific picture in mind, I’ve found it challenging to explain who I am and who I am becoming. In a lot of ways I’m just the me you already know, there really isn’t that much different. It’s not like my declaration has suddenly been followed by sunbonnets and sundresses (nothing wrong with that, just mostly hasn’t been my story). I’ve flirted with the non-binary label and I think certainly some of that applies to me (I do use they/them pronouns) but I identify as feminine. But…I hate makeup. But this, but that…lots of exceptions and qualifiers. All of the pieces and markers that mark me as male or female are getting mixed up, and for now I’m mostly content seeing where that takes me. I’m a trans woman who wants to wear Carhartt’s and cut wood. I’m a non-binary person and like hanging with NB queer folks. I have Poshmark and Stitchfix accounts. I’m okay with my face one day, and the next all I can see is an old dude with sagging jowls. Dysphoria comes and goes in waves.

I think that this ongoing process, where transition is a journey that meanders rather than flies like a crow to the final destination, is what is confusing for many when I talk about this stuff.

My narrative of transition doesn’t seem to fit the ones you read about in the papers, where guy comes out as trans, goes away one weekend and comes back to work Monday a woman, complete with a discarded deadname, and an embrace of their new authentic self. That narrative is easy to understand because it’s like gender is a switch you flip, and you’re not challenged by what happens between - the gender binary remains intact.

I don’t have a deadname. “Colin” isn’t dead to me, it’s who I’ve been for 51 years, and I’m proud of both the name and the life. Yes, I am reaching for authenticity, but to me being authentic is about merging all of the parts of me so that I don’t have to leave any part hidden, denied or damaged. It’s about setting aside the persona and embracing the person.

Certainly as a trans person there has been a bit of persona, a front created to fit into the part of the gendered world I was by default assigned to.

But I was, and am, still me. A changing me.

I can declare that but the truth is we all change, all the time. We’re never not changing, it’s just that because yesterday was kind of like today and tomorrow looks to be similar, we think that our own identity day-to-day is fixed. Kind of like the moon traversing the sky, we mostly change too slowly to know that it’s happening.

In that way, transitioning is a gift. I get to embrace the change that was happening anyway, and my intentionality guides it.

I still don’t know the full story of what happens next.

But really, who does?

And does it help any to pretend we do?

Hi.

Hey folks!

I changed the URL for my website to match my name a few weeks back; then I posted something here and then deleted it. Then I posted on Instagram, and that’s still up, so I guess I’m back to explaining things over here.

If you’re not new to me or my work, then you know I’ve gone by Colin Keefe for 51 years. Now it’s Colleen Harriet. I’m okay with just “Col” too.

I’m transgender. I’ve been coming out in stages over the past two-plus years, a sort of stop-start, push-pull process whose pace has been tied to the growing strength of my own self-acceptance.

I haven’t made work in over a year. I miss it. I’ve never in my adult life paused my studio practice before, but it was needed.

I’m re-establishing a studio practice this spring, but I think what comes out of the studio doors will look different from what came before. I’m looking forward to that. I’ve long felt a need for more agency and freedom within the creative rules I’d set for myself. Now I’ve come to realize that that agency and freedom is not just a lesson for the studio but for life.

Best,

Colleen

Early blender experiments...

Read MoreRecapping the opening reception for Still Time: Tom Judd, Cindy Stockton Moore and James Rosenthal

Read MoreI'll be having an open studio (along with my wife Andrea Wohl Keefe) on 10/14 from 12-6 PM as part of Philadelphia Open Studio Tours.

Hope you can join us!

A week or so back, at the invitation of CFEVA and Artist and Craftsman in Chestnut Hill, I did a two hour drawing demo in the store. Mae Belle Vargas took the photos here. That's my son working on the other drawing table.

CFEVA is the organization behind several fellowships and Philadelphia Open Studio Tours, which Andi and I have participated in for 9 years.

Artist & Craftsman is an ESOP company, wholly owned by the employees. I'm a socialist basically so if a company's owned by its workers my business goes there. So should yours!

Not really blogging much, am I? Here's some new stuff.

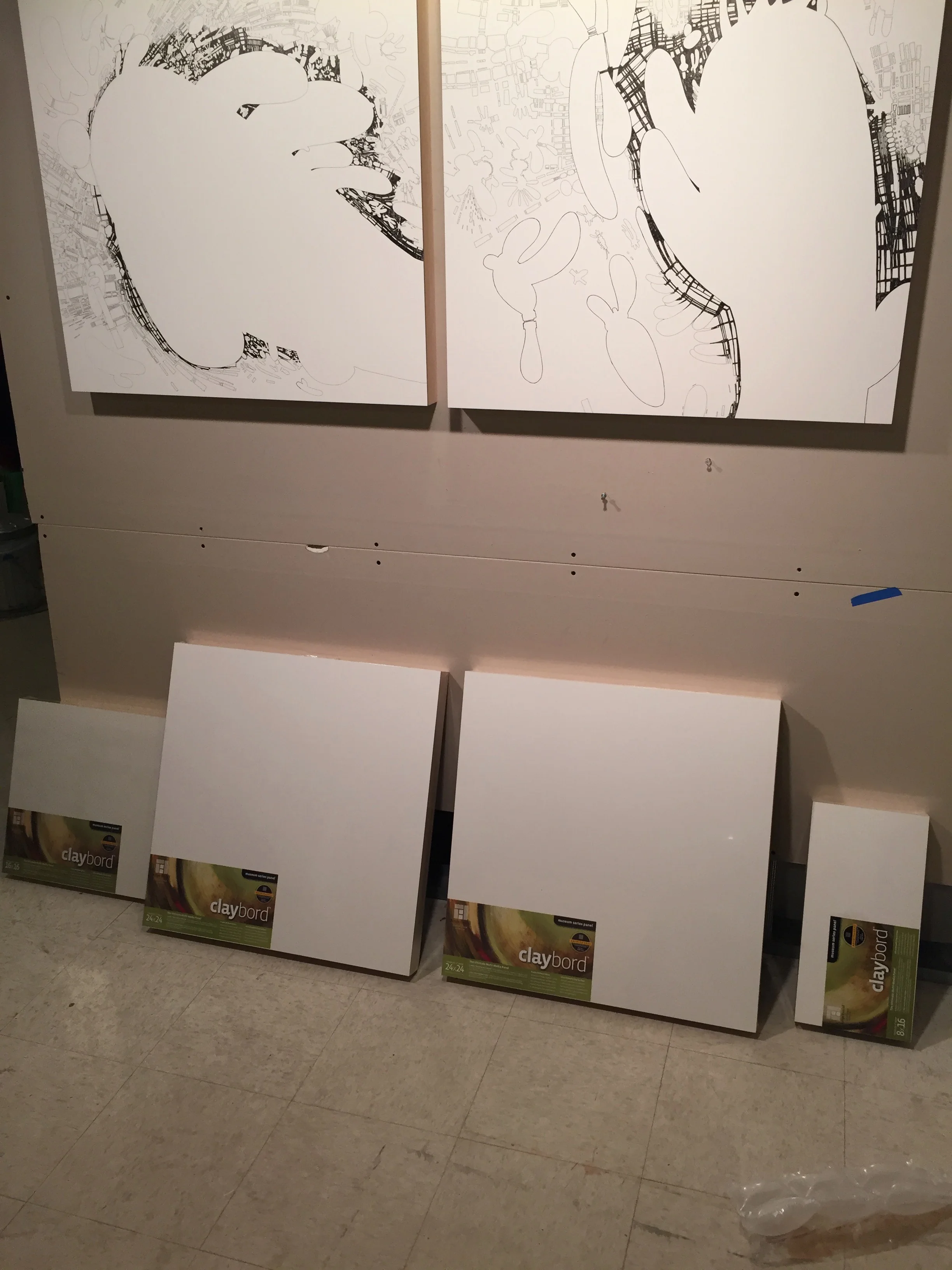

Here's a quick video of how I work. The two large (30"x30") panels are part of a new series on panels of various sizes.

One of my goals is to reduce expenses, so I can end each year in the black with respect to art income. If your work requires framing, this becomes a large chunk of change that you have to overcome in a given year. I can easily drop $2000 in framing costs on a show.

So...I'm experimenting with Ampersand Claybord pre-fab panels. The surface is advertised as archival, and it's silk smooth, so perfect for the Micron ink pens I use. And they don't require framing!

Here are some work in progress photos from a 2 panel piece I'm working on. One thing I'm not entirely happy with is the fact that the frames bow inward slightly due to shrinkage, so I can't butt these up together without a 1/16" gap in the middle of the seam. I'll have to present with 1/4" separating or something. I've also considered rotating the panels or hanging much further apart...

Andi and I dropped by James Rosenthal's studio last Sunday. James is an extremely prolific painter, sculptor, writer and musician based in Northwest Philadelphia whose work and output are outsized compared to his relative local exposure (another way of saying this guy ought to have more shows). It's great stuff.

More about James:

Anybody who's been in this game longer than a few years knows keeping track of what's been made, who has it, what sold, when it's due back etc. etc. is

a. An incredible pain in the butt.

b. Absolutely critical.

It's also one of those business-y things that (at least when I was in school) was never taught because it was about business and business was bad. On one level it makes sense not to focus on business execution in art school - there's so much to assimilate and internalize and do to obtain any kind of mastery in an artmaking, that without that kind of focus purely on art, students may come out unprepared to actually have a studio practice that's meaningful.

I don't want to imply that my college instructors didn't have advice - they were great. Ron Leax (who just retired), my sculpture instructor at Washington University, taught me core critical thinking and craft. And Heather McGill, my instructor at Cranbrook (who ALSO just retired!) on top of critical thinking taught all of us to work hard, and told us to move to New York. It was probably much easier advice to follow in the 90s than it is now! But for better or worse, folks in my cohort came out of school with little sense of how to proceed in the art world, or how to organize our output in a way that would be maintainable over a lifetime.

The bottom line is that any kind of creative practice needs to have discipline in order to continue. There's the grit one must have to go to the studio regularly, the stomach for continued and ongoing rejection, and the determination to move through self-doubt to confidence in value of one's work over a period of years. That part can be learned by example - looking to models who you want to emulate and seeing how they did it.

And then there are just nuts-and-bolts basic business things that keep your studio practice organized. And artwork inventory management is one of them.

I use a solution I built in FileMaker for this over a period of many years - since the late 90s - but I'm sort of an oddball case because my day jobs have all revolved around FileMaker (as a software developer or project manager), so I've had access to the tools and knew how to leverage them. Also, I'm a nerd and track my studio time to the minute when I work on a drawing, and what art inventory management tool is going to tell me Cloud City took 66.93 hours?

None of them, sadly.

So...what do you do if you don't have access to a $329 software package and a day job doing database design - and have normal artist needs unlike me?

There are plenty of other ways to skin the cat, some free, some paid.

The landscape of art-specific inventory management systems is pretty uneven, with some expensive options that have a ton of features, and some more reasonable offerings. There's a more comprehensive round up from 2015 on Christine Wong's blog here: Artist's Inventory Software Reviewed that has some products I don't really know much about. Her comments about a lack of exhibition history tracking in Artworkarchive.com have been addressed since that posting, but she makes good points in general about the tradeoff between light and robust feature sets. With that in mind I thought I'd call out a beast in terms of functionality (and price) and compare. More below.

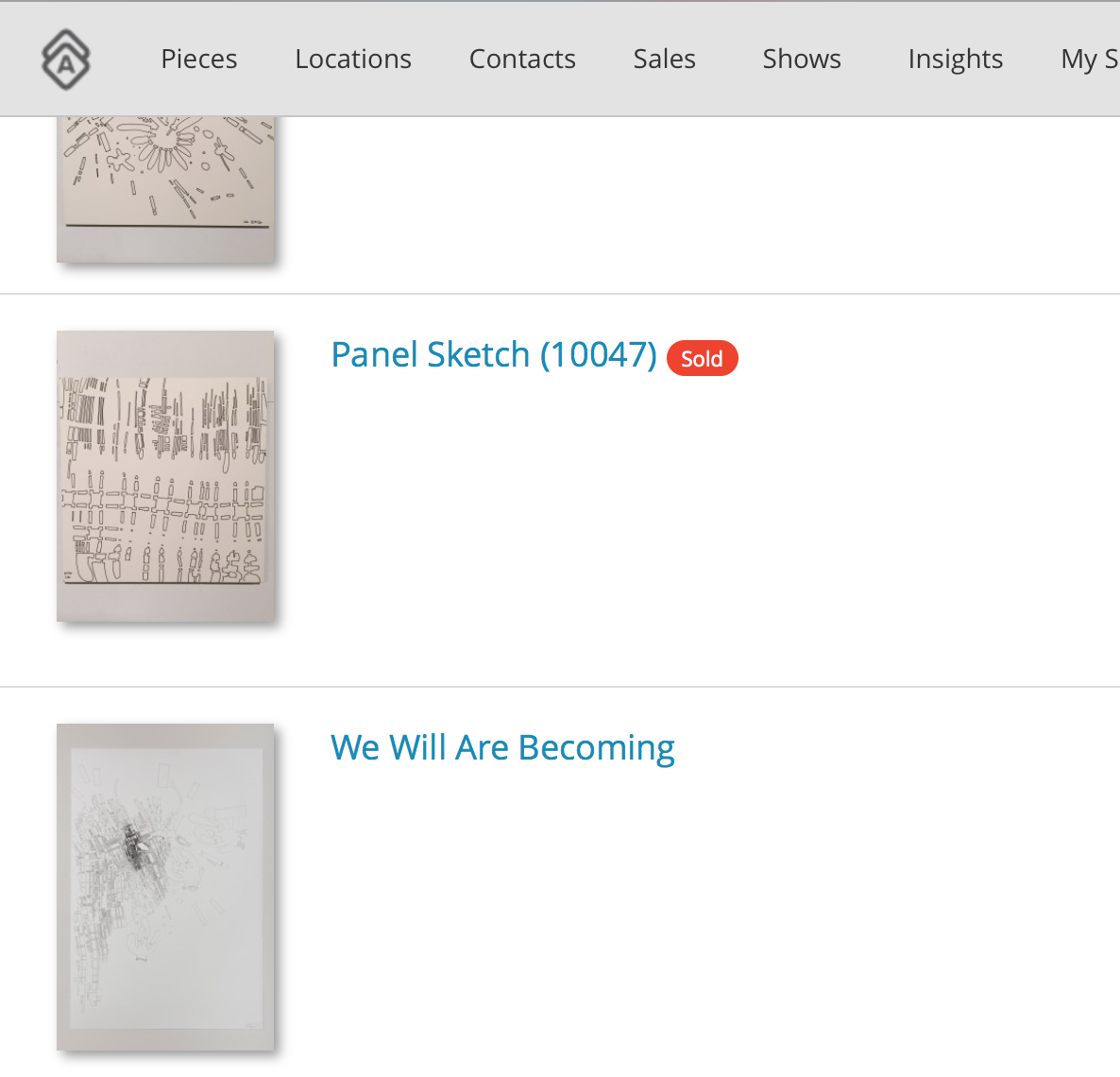

ArtworkArchive.com is a SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) offering that's been around for several years, and has a robust set of inventory management features, as well as some light contact management, good sales tracking that understands editioning, and interesting dashboarding/reporting tools. At the professional tier you can also use it for document management (say, attaching condition reports or consignment forms that you received via email or scan to an artwork record).

They also have an artists' profile directory service that's part of the core package, which is searchable by medium and region.

In my opinion it's the best option for those starting out, the pricing tiers offer room to grow, and it's very reasonably priced - the mid-tier "Professional" level is $108/year.

Artworkarchive.com pricing tiers:

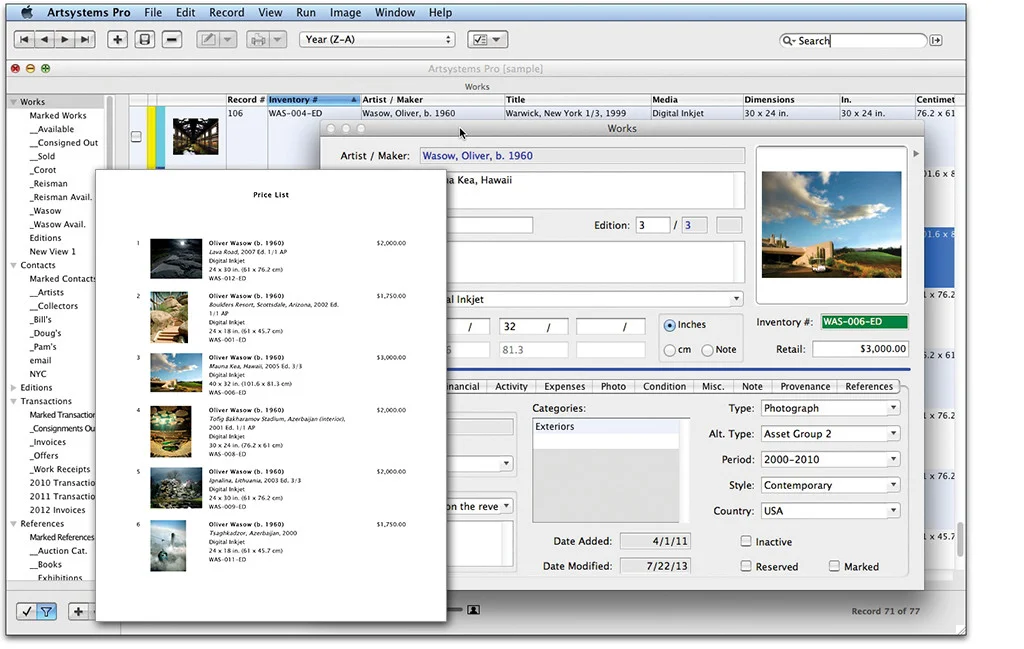

Artsystems has been around since 1989. Their product line focuses on several channels and is customized for each: galleries, private collections, institutional collections and artists.

Their artist specific offering, StudioPro, can be compared to artworkarchive this way: it's much more expensive, but provides MUCH more robust business management tools. Here's the pricing model. Note that the monthly charge is $99, vs $9 for artworkarchive.com.

There's a reason for that price difference: StudioPro is designed for studio practices that require a much more business-based approach. I'll give an example by comparing the way the two products handle sales.

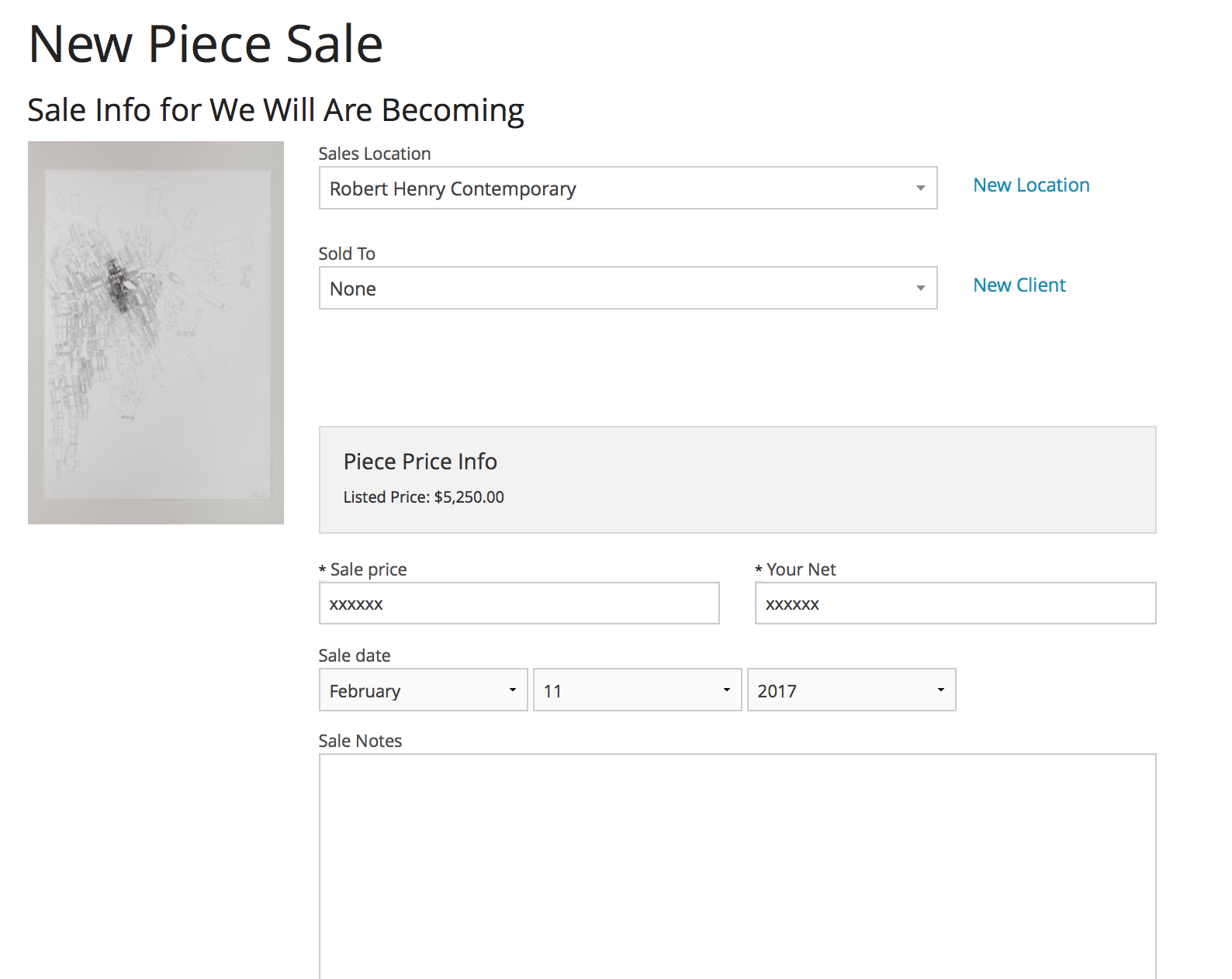

Here's how artworkarchive.com does it.

artworkarchive.com Sale entry

It's got the basics you want: who did it sell to, for how much, who sold it, and what your net was. It's simple and easy to use, with a modern, clean UX, which makes it a pleasure to interact with.

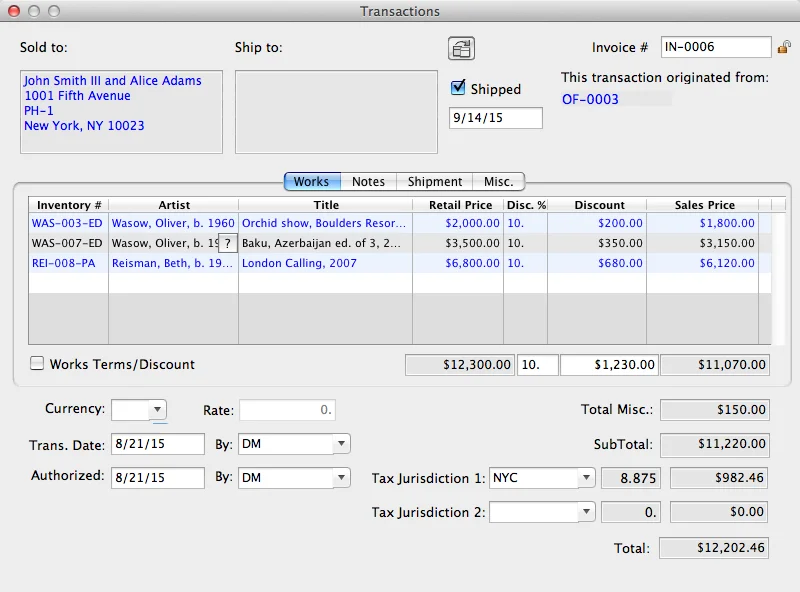

Here's StudioPro:

StudioPro Invoice Entry

One look and it's easy to recognize how much more goes into a sale than a few key fields. Currency, tax jurisdiction, multiple items on a single sales invoice, shipment tracking, discounting and so on. Good business tools help you adhere to straightforward business practices. QuickBooks for example is the industry standard in accounting because it models accounting so perfectly.

Still, why so much more for a product like this? The bottom line in software development is the more features you support, the more expensive your product is to maintain - it just costs more to make artsystems products. Artworkarchive.com can offer a lower pricing tier because their product does fewer things - the surface area of things to debug, refactor and regression test when you add something new is just much smaller (and therefore cheaper) to support. There's no wrong answer in pricing, and essentially these are two different products for different ends of the market.

I think the key takeaway here is that if your studio practice is generating a significant amount of sales or management overhead, you may want to look at a robust business management package like StudioPro. If you just need a simple way to organize your studio and manage sales (or like a streamlined experience) ArtworkArchive.com is probably the way to go.

There are lots of other options out there that, frankly, I haven't done research on. The following two cloud based solutions are priced in the mid-range and probably offer more features than artworkarchive.com - and less than artsystems.

Masterpiece Manager - cloud based, $19/month - I see this one recommended quite a bit.

Artcloud - cloud based, $19/month

I'll make the obvious point here that Google Sheets can be used for all of this if you don't mind keeping track of things in a very manual, list oriented way.

But if you're looking for a target application in the free software space, there appear to be options. I haven't dug into them yet so will save that for a followup post. Here's what I'll be looking at (so far). Let me know if I should look at anything else!

http://www.collectiveaccess.org

There's a great show at Snyderman Works Gallery that opened Friday, called "Paper Work", curated by Alex Conner. It's a large, sprawling exhibition that includes conventional works on paper and sculptural constructions as well. Andi and I had favorites: Lucia Thome and Terri Saulin Frock.

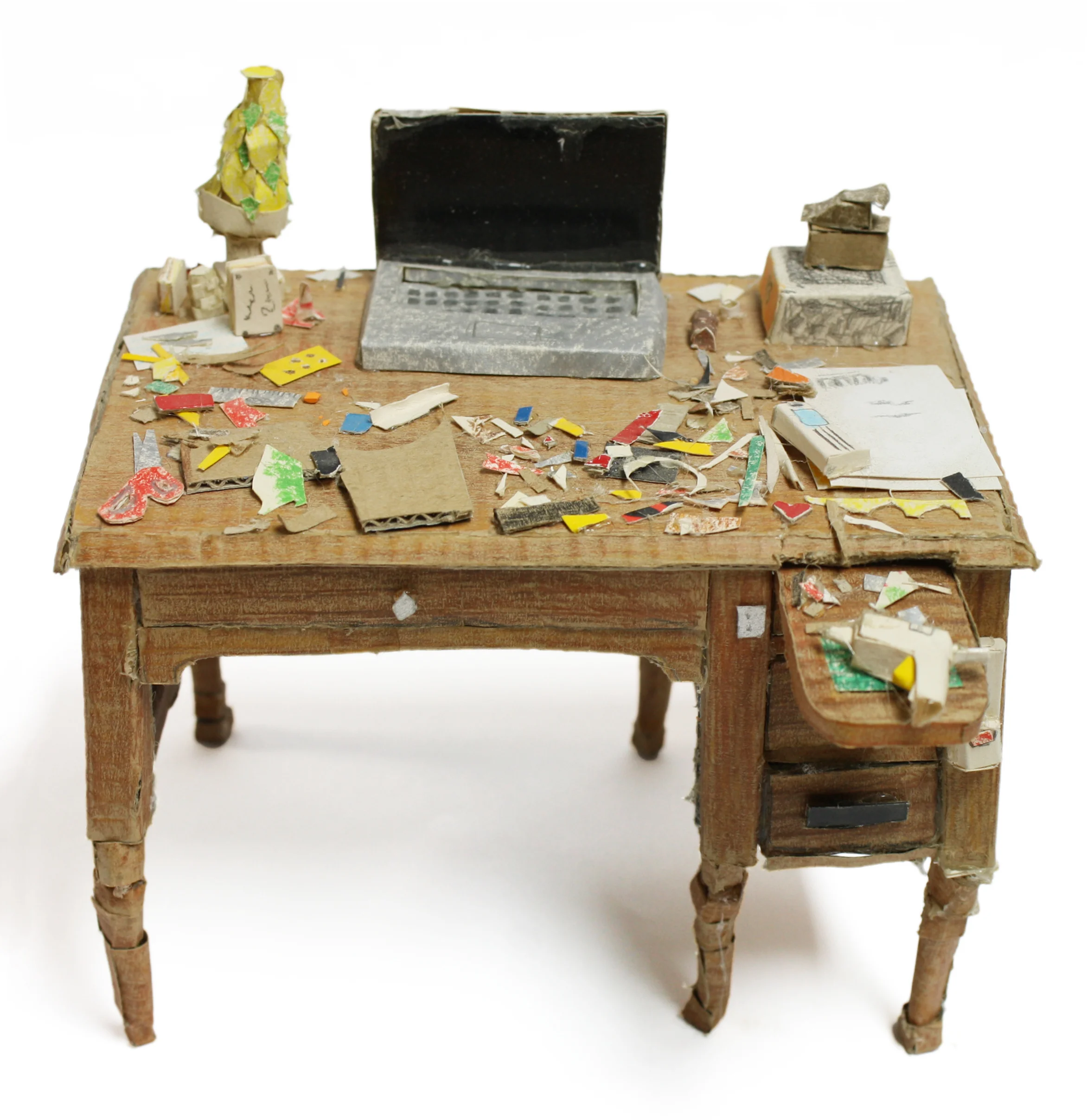

Lucia Thome, Desk, Paper Construction, 5.5"x 4" x 4", 2016

Terri Saulin Frock, Body Without Organs/Wasp Traces Orchid, Ink on Denril, 60"x 24", 2015

Tear it Up, Tear it Down is a 3 person video show at Grizzly Grizzly that's frenetic and engaging, and includes stop-motion, collage and digital animation: Kelly Sears, Kelly Gallagher, and Martha Colburn. My photos sucked, but here are two opening shots. Wish I could credit who is who here, I'd have to go back and see it again (it's worth a visit!).

So here's an oddly comforting/motivating/bleak thought:

I'm edging toward my fifth decade of life, and have been thinking about how to use what's left to me. We only get so much time on this earth, and when the clock runs out, how do we jibe what happened, what we did in that time, with what we wanted?

The calendar's ticking too.

For me, especially lately, it means refocusing how I use that time toward the things I want now, so I can't say later that that time was wasted doing what others wanted instead.

I have kept track of my studio time since 1998 or so, with a few gaps in record-keeping in the mid 2000s.

I've always thought of this in the way you might think of a FitBit - you can't improve what you don't measure, and clocking time gives me something to game, to better. Can I put more time in the studio this year than last year?

But increasingly time has come to mean something different to me. It's not how much I've banked, it's how much I have left to spend, and how not to squander it.

2017 is about this.